Have we made an idol of families?

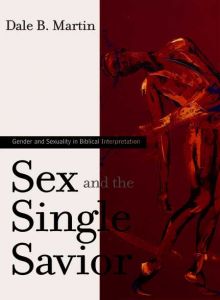

‘How can we idealise marriage and the nuclear family while clinging to a saviour who was unmarried and without issue?’

In Sex and the Single Savior, Dale Martin asks an important question: have we made an idol of families? Our knee-jerk reaction is to say, ‘‘Of course not’. But Martin reminds us that sometimes we cling to theologically-phrased excuses for what we do, rather than examine what the Bible actually says. When it comes to the importance we attribute to the family (in conversation at least, even though our practice may undermine our ‘theology’), Martin asks how can we idealise marriage and the nuclear family while clinging to a saviour who was unmarried and without issue?

The book brings together a number of Martin’s previously published articles to get to grips with a number of issues that have to do with gender and sexuality. He examines what classical and early Christian writers would have understood by the Galatians passage which referes to there being no male and female in Christ. He discusses how odd Jesus’ celibacy would have appeared to his contemporaries. But the most provocative chapter, as far as the family is concerned, is the eighth chapter, ‘Familiar Idolatry and the Christian Case against Marriage’.

Martin begins the chapter with a bold announcement that mainstream Western Christianity (Catholic and Protestant, liberal and conservative) has made an idol of marriage and the family. It is a strong claim but we would have to agree with him that those who do not fit the nuclear family ‘ideal’ usually find themselves on the fringes of church life. Martin supports his claim by turning both to the New Testament and to the writings of the early Church. He suggests that the early Church was culturally much closer to the New Testament period and so they are better placed to understand the intention of the Biblical texts than modern theologians.

Martin starts with Mark 3 and points out that whatever Jesus taught about family, it must sit hand-in-glove with the way that he prioritised time with a group who shared his religious convictions over time with his family. He upheld the fifth commandment but at the same time he taught that this newly founded ‘family of God’ had a higher claim on his followers’ loyalty than any that might come from their family of origin. Jesus and the early Church not only took a strong stand against divorce, they went much further, ruling out marriage in the new age. Jesus’ singleness could simply be an accident of history, an indication that he had simply not got round to marriage by the time he died. But when we line it up with the teaching of the earliest Church it seems more likely that it was the result of a deliberate decision not to get married. As the famous Bishop and preacher John Chrysostom pointed out, why would you need marriage where there is no death and therefore no need to have children? Martin argues that household and family, together with its hierarchy are part of the old world order that Jesus came to dismantle and overturn. In its place, he establishes a new community founded on different values and grown through spiritual birth rather than natural birth.

In Luke and Acts Martin finds fertile ground to explore this theme. He argues that the later books of the New Testament dilute it down in favour of teachings that were more at home in family-friendly Greco-Roman culture. Martin is a good communicator and his arguments have a certain appeal, especially in the way that he draws our attention to passages and texts that we have overlooked because they didn’t fit our family values. But it in his selection of material from Church history that we realise that he is being just as selective as we were, and prefers obscure and minority texts rather that those whose names appear in any of the standard texts on Church history.

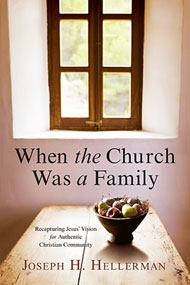

Martin has opened our eyes to see the need for a careful and sympathetic review of the Biblical literature—all the Biblical literature. He is right when he says that we need to think again about what it means to us that Jesus was single. We need to look again at the way we promote and practice family. But Martin might not be the best one to help us to do it. For me, Hellerman’s When the Church Was a Family is much better at explaining how we might consider church and family together in a more Biblical fashion.

Like Martin’s Sex and the Single Savior, Hellerman draws our attention to some of the more ‘anti-family’ statements in the Gospels (for example, Mark 1:14–20; 3:31–35; Matthew 10:34–38) and acknowledges that we would prefer to explain away the anxiety that we feel by talking about ‘hyperbole’ or saying that it is a matter of emphasis and priority but that these things don’t actually tell us to adjust our behaviours (pp 54–56). Like Martin he attempts to re-read the passages in the light of the first century thought world, but while Martin has first century attitudes to sex and sexuality in mind, Hellerman examines the text in the light of collectivist nature of first century culture.

Like Martin’s Sex and the Single Savior, Hellerman draws our attention to some of the more ‘anti-family’ statements in the Gospels (for example, Mark 1:14–20; 3:31–35; Matthew 10:34–38) and acknowledges that we would prefer to explain away the anxiety that we feel by talking about ‘hyperbole’ or saying that it is a matter of emphasis and priority but that these things don’t actually tell us to adjust our behaviours (pp 54–56). Like Martin he attempts to re-read the passages in the light of the first century thought world, but while Martin has first century attitudes to sex and sexuality in mind, Hellerman examines the text in the light of collectivist nature of first century culture.

Western culture is individualistic. Top priority is given to the individual—to me and my agenda. This means that an individual is relatively free to jump from group to group according to present needs and circumstances. The same attitudes are carried over into the religious sphere so that spirituality is first and foremost about my relationship with God. Salvation is about how he has saved me. But Hellerman points out that the first century Mediterranean family was collectivist in outlook. He identifies three elements of the perspective:

- The group takes priority over the individual.

- The most important group is the family.

- The most important relationships within the family were sibling to sibling relationships.

Read in this light, Jesus is not saying that the family is unimportant. The pro-family sections of his teaching confirm this. Rather what Jesus would have been heard to have been saying is that family-like relationships within the people of God take precedence over our responsibility to, what we might call, our families of origin (p 65). Our priorities can no longer be God > family > church > others, which Hellerman suggests is the default setting for most American evangelicals. Rather Jesus’ invitation is for us to re-order our lives according to the pattern God’s family > family of origin > others. He says that for someone living in the first century, it was impossible to think in terms of a commitment to God without including a commitment to his family. It is impossible to separate my responsibility to my church family from my responsibility to God and inconceivable to insert commitment to family of origin in between the two (pp 72–74).

When we turn to the outworking of Jesus’ revolutionary instruction in Acts and the Epistles we find four features that tie in well with Hellerman’s point:

- Emotional solidarity

Emotional bonds between believers: 1 Corinthians 16:20; 2 Corinthians 2:12–13; Philippians 2:25–28; 1 Thessalonians 2:17–3:8; Hellerman pp 79-82 - Family unity

Expectations of unity and harmony between believers with no discord: 1 Corinthians 1:10–11; 6:1–8; 2 Corinthians 13:11; Ephesians 4:3–6; Hellerman pp 82–85 - Material solidarity

Sharing of resources: Acts 11:27–30; 1 Corinthians 16:1–4; 2 Corinthians 8:1–2, 13–15, 22–23; Hellerman pp 85–89 - Family loyalty

Undivided commitment to the group: 1 Corinthians 7:10–16; Ephesians 5:21–6:9; Hellerman pp 89–95

Hellerman also examines other early Christian writings and finds confirmation for his revisionist views. So the prominent Christian apologist Tertullian wrote, ‘we call ourselves brothers ... so we, who are united in mind and soul have no hesitation about sharing what we have. Everything is in common among us, except our wives’. Apologeticus 39:8–11.

Hellerman ends with a consideration of how the church might look and operate if we were to embrace this collectivist mentality. One of the areas that might be transformed, he suggests, is our evangelism. He suggests that the Gospel announces that (i) we have been delivered from the penalty of sin in our past, that (ii) we are being delivered from the power of sin in our present and that (iii) we shall be delivered from the presence of sin in our future. He suggests that within an individualist framework we invite people to accept (i) so that they can commit to Christ and experience (ii) as they look forward to the hope of knowing (iii). Two ways to Live is an example of an evangelism tool that draws on this scheme. Hellerman suggests that, from a collectivist perspective, it might be better to think in terms of (ii) then (i) and then (iii). We invite people to participate in the life of the Church and, as they warm to it and to our brothers and sisters, they begin to see Jesus’ power over our sin and selfishness. And then experiencing something of it working in their own lives, this leads them to giving themselves to Jesus and to realising the significance of his achievement on the cross on our behalf, as they increasingly look forward to the consummation of all things at his return (pp 120–143). Apart from the fact that it is a lot more consistent with the Bible, I wonder if there is something in this, particularly for Gen-Y and the new millennials who are said to be more community-focused than the Baby Boomer generation which produced Two Ways To Live. It would mean, however, that we in the Church must learn to put aside our petty squabbles, for the sake of Christ, and learn to love each other.

‘A new command I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another. By this all people will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another.’ John 13:34–35

For more articles from Growing Faith, subscribe to our monthly e-newsletter.

To hear about the latest books and resources from Youthworks Media, subscribe here.